Coping in times of adversity

The new war-related stress instills just as we come down from a dizzying height on the two-year roller coaster ride of COVID-19, and it is no surprise that so many of us feel confused and hopeless. Many people still have unprocessed anxiety, grief, and loss from the pandemic years, and it seems like bad news are here to stay.

Disturbing. Inspiring. Overwhelming. Faith-restoring. Anxiety-provoking.

The news and social media posts from Ukraine and neighboring countries are all of the above, and more, but what can we do when we’re exposed to too much information, when it feels like things are getting harder and harder to handle?

Stress can come in all shapes and sizes, and in the last section of the article I will state a few strategies for coping with it that can be adapted to your situation, but the main focus of this article will however be the stress caused by the present context of the war, together with the 2-year background of exposure to potentially traumatic information shared in the news.

The psychologist, lecturer, and researcher Daniel David gives us a simple, yet powerful advice - people should move on with their lives, adding that “it is the biggest blow to hatred/war - but still rational in regards to danger and its evolution”.

In times like these, it is impossible to remain indifferent, and it is not considered unhealthy to experience a certain level of distress or negative emotions as long as they are still functional. Even more, having positive emotions only or emotionally detaching from the reality of things could be signs of maladaptiveness. Instead of seeing the spectrum of functional, healthy emotions in terms of black and white, try to look at it in a more flexible way. It is okay to be sad, concerned, uncontemplated with how things are going. These are different than depressed, panicked, or aggressive, and will encourage you to take action and to engage in functional behaviors.

Little Immersion in Psychology

The Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) puts it quite simply - stress is the product of a transaction between a person (including its multiple systems: cognitive, physiological, affective, psychological, neurological) and his or her complex environment. The way a person perceives a stressor determines the way they cope with it or respond to it. A series of contextual factors, such as abilities, resources, or cultural norms will influence the level of discomfort or distress caused by the stressor and whether or not it is seen as a threat. If a situation is perceived as having big personal implications, but the requirements of the situation exceed the coping resources available at that time, the person will feel stressed.

Stress is contextual, meaning it involves the interaction between the person and its environment, it is dynamic, meaning it fluctuates in time, and it can manifest both on a psychological and physiological level (Violanti, 2010). We all lived it or saw it in others, and we know that stress is often accompanied by fatigue (Strahler & Luft, 2019) and impaired mood (Giessing et al., 2019).

Put a name on it.

Yes, for many people it might be stress that is taking over their lives these days. However, stress is not a sign of weakness, something that should be covered or ignored, but rather something that needs to be identified and addressed. Stress for sure doesn’t follow a very mathematical approach when it decides to lurk in, but overcoming stress can be viewed as a sort of an equation.

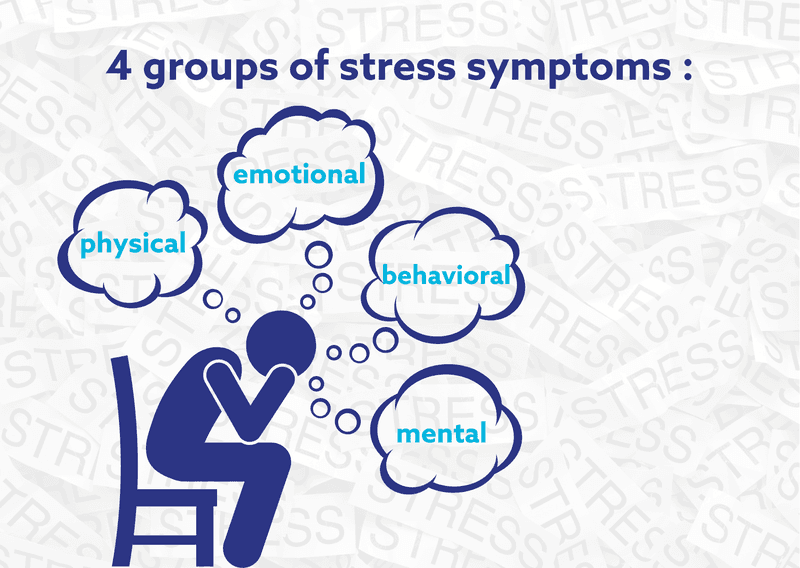

Stress has three elements: 1. the stressor or source of stress; 2. the perception or how you interpret the stress (based on the perception you have over your coping resources, the way Lazarus and Folkman said it); and 3. the response or how your body registers the stress. Begin by identifying the way you react to stress. Stress symptoms can be categorized into four groups:

Physical: headaches, fatigue or tiredness, sore or tense muscles, stomach distress, rapid heartbeat, cold sweat, shaking or trembling

Emotional: angry, resentful, depressed, fearful, irritable, tensed, frustrated, panicked, overwhelmed, helpless, hopeless about the future, feeling trapped

Mental: racing thoughts, difficulty making decisions, trouble concentrating, poor memory, dwelling on problems, negative thoughts about self, confusion, daydreaming, wandering thoughts

Behavioral: wasting time, withdrawal, increased quietness, jumping from one activity to another, impatience, temper outbursts, crying, unusual eating and/or sleeping patterns, escapism, avoiding important tasksNow that you know your responses to stress, try to find out where they come from. This can be more difficult than it appears to be, and the stressors can be a perfectly disguised combination of many factors. Is it the emotional stressors, such as worries, fear, anxiety, low self-worth, that put the cherry on top? Is it the family stressors, or the financial ones? Change stressors, like having to change your job, exit/enter a relationship, moving somewhere else? Work stressors, like relationships with co-workers, job insecurity, unemployment, getting back to work? Is it social stressors, which include personal aspects like relationships, someone’s expectations of you, feelings of social inadequacy, or collective aspects, such as impactful events and their repercussions (think pandemic or war)? These are just a few examples, but each individual has a unique mixture of present and past factors that, when added up in just the “right” amount and triggered by just the “right” situation can let the stress flow freely.

How to get back on track

- Have a rational approach towards bad news (Daniel David):

1) evaluate the potential threat as “bad”, or even “extremely bad”, but not “the worst” or “catastrophic”

2) focus on finding solutions, rather than psychologically amplifying the event affecting you

3) choose to evaluate specific aspects of situations and not the situations globally. - Engage in problem-solving. This is a great coping strategy because it shifts your attention from what goes wrong to what stands in your power. Write down the problem as clear as possible. Keep in mind, the problem is not the external situation, but your response to it. So saying that the war is the problem will be tricky, to say the least, if you stopping it is not one of the solutions. The problem might be you procrastinating on tasks, or binge reading/watching the news. The next step is to brainstorm all possible solutions. Write down all the possible consequences too for each solution and ask yourself “If I did this, can I live with what happens?”. For example, if you choose to say no to taking over some tasks from your colleagues, would you be able to accept the (irrational) thoughts of not doing enough/being a bad colleague? You might even talk it over with a friend or someone you trust, before picking your best alternative. Now it’s time to test it! Try to implement your solution and see how it works, how it makes you feel, and what cognitive and emotional benefits it has. And if something doesn’t sit quite right with you while doing it, problem solve again - flexibility will be your best friend.

- Cognitive restructuring. Remember from the Transactional Stress Theory that stress is mainly produced by the way we perceive our available coping resources regarding a given context. Following the same line of thought, cognitive psychology is telling us that what stands between a stressor and the consequences we experience (be it cognitive, emotional, physical, or behavioral) is the way we think about/interpret the stressor. One way to restructure your dysfunctional beliefs is to dispute them from an empirical perspective (What proofs do I have that the information portrayed by the media always mirrors reality?), a logical one (Is it logical to think that this is the worst thing that could happen? aka what other extremely bad things could happen), or a pragmatical one (How does it help me to binge read the news for days in a row?).

- Challenge previously held beliefs that are no longer adaptive. This comes as a continuation of the previous point but with an emphasis on the fact that what may stand true in times of normality, might not be available when big or impactful events occur. Thoughts like “I must have a balanced environment to focus well”, “This shouldn’t happen right now”, “Life should be beautiful, peaceful, and relaxing”, “It is not fair to go through a war right after 2-years of a stressful pandemic” are inflexible beliefs that could hold you back from adapting to distress and from taking action to thrive in the new context.

- If you’re glued to the news, unstick a bit. It’s good to not be in your own bubble and to know what is happening in the world, and it is hard to look away from the news when such compelling images and videos are shown, but it is also important to pull yourself away. Remind yourself that you don’t have to know everything that’s going on, and set time limits for yourself in terms of how much time you’re consuming news, and from what sources. Repeated exposure to this kind of content can be distressing, overwhelming, or numbing, and information from crisis zones can often be inaccurate or incomplete. Get up to date with what is happening if you feel like you need it, but then unplug and go on with your life and your duties. If we all stop from our routines and we get into an aimless state, we will only worsen the situation.

- Reconnect to your body. We want to be regarded as highly evolved, cognitive beings, but the truth is we are also very much physical. Disconnecting from our physical nature is nothing but a big threat to our mental health. Find a sport you like, engage in a fun or relaxing activity outside, give some extra attention to your nutrition and sleeping habits. All these won’t make you less of an intellectual, but they will for sure contribute to a better psychological state and will support you in your day-to-day tasks.

- Talk to people & maintain emotionally supportive relationships. A problem shared is a problem halved, and talking about your anxiety can help you work through the emotions and perhaps get a clearer perspective (Lemaire & Wallace, 2010). Sometimes, just talking it out is what you need, but there’s also the be, other people may have a different take on a news story or the future outcome, and hearing their point of view could help you find a balanced perspective.

- The bright side. Look at the humanitarian spirit that this crisis is bringing out. What is happening right now is overwhelming and to be honest, terrifying, but there’s a little light at the end of the tunnel, and that is the humanity in people, the way they all got their forces together to help the cause in their own way. It is encouraging, maybe even inspiring, or motivational for some, and definitely a call to action to take responsibility for the situation and do your little part by keeping a balanced, solution-oriented attitude in front of adversities.

Resources:

- Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

- Lemaire, J.B., Wallace, J.E. Not all coping strategies are created equal: a mixed-methods study exploring physicians' self-reported coping strategies. BMC Health Serv Res 10, 208 (2010).

- Murthy, R. S., & Lakshminarayana, R. (2006). Mental health consequences of war: a brief review of research findings. World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 5(1), 25–30.

- Violanti, J. M. (2010). Dying for work: stress and health in policing. Gazette, 72, 20-21.

- Strahler, J., & Luft, C. (2019). N-of-1-Study: A concept of acute and chronic stress research using the example of ballroom dancing. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 29, 1040–1049.

- Giessing, L., Frenkel, M. O., Zinner, C., Rummel, J., Nieuwenhuys, A., Kasperk, C., … Plessner, H. (2019). Effects of coping-related traits and psychophysiological stress responses on police recruits’ shooting behavior in reality-based scenarios. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1523.

Introducing the developer’s

console.

Sign up to our newsletter and you will receive periodic updates of new blog posts, contests, events and job opportunities.